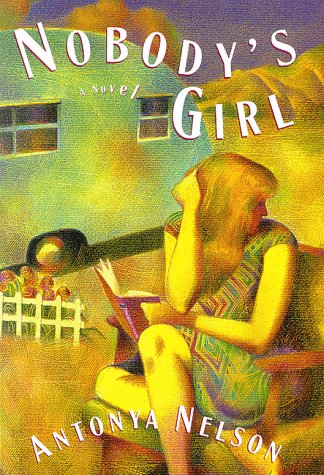

Items related to Nobodys Girl

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1

"Miz Stone," the pregnant girl said in the way Birdy hated: here at Pinetop High, teachers came in either Missus or Miss. "Miz Stone," the pregnant girl repeated, her hand swaying forlornly, every part of her weary. "Why are all these stories and poems so depressing?" As evidence, she now hefted the reader so that it fell splayed from her palm, a fat textbook covered with the bored graffiti of her predecessors, so heavy it appeared to be taxing her frail wrist just to hold it up. Outside, snow fell. Not the snow of November or December, which portended Christmas, nor the snow of January or February, which meant skiing, but the snow of March, that defeated, dreary, superfluous month no one could love.

Weather and room and subject matter were all gloomy. Birdy had smoked a joint over lunch break with her colleague Jesuús Morales, and that, combined with the pregnant girl's question, the snow, and the body odor of twenty-three teenagers, made her feel hopeless for humanity. She ached for the girl anyway, so unprepared for what awaited her. Around the teachers' lounge, her plight had become a watershed: those who sympathized and those who judged. As the youngest teachers, Jesús and Birdy were inclined to identify with the students.

Birdy drew a big breath as if to blow out candles; her tongue still tasted dryly of pot. She explained to her senior lit class that, in the first place, the stories and poems weren't all depressing, and, in the second place, didn't tragic feelings linger longer? Would there be anything much to say about a happy day? Her students studied her, thinking of a thousand things to say about a happy day. A few of the girls thought she had nice clothes; the boys appreciated her long legs and long hair and the way she took jokes well. But they couldn't quite muster the enthusiasm she seemed to expect. Accustomed to Spanish pronunciation, they called novels "nobbles," reducing them to rabbit food. They all hopped to action in other classes, inspired by threats, eager to keep athletic eligibility, avidly cheating if necessary. But Ms. Birdy Stone, lover of sad literature, held no particular power; her class was good for relaxing. This afternoon she felt her kinship with her students develop a wrinkle, a space between her and them, an annoyance that was new to her. I'm getting old, she thought dejectedly. They'll all stay seventeen, year in, year out, but soon I'll be old enough to be their mother.

Everyone sat waiting for the bell, which wasn't a bell at all but a buzz like an oven timer. Inside the school it was unnaturally hot; they were done. The buzzer buzzed and they went away.

All small towns are not alike. Having seen one, you had not seen them all. Everyone did not know everyone else's business, and the people were neither friendlier nor more genuine, the lifestyle not purer -- just duller. Birdy Stone had lived for nineteen months in Pinetop, New Mexico, and still the old adages were being debunked.

She'd come from a big city, Chicago, and thought a high percentage of its inhabitants would fit right into Pinetop, far, far better than she did. She still tended to think of herself as temporarily installed here, not like a tourist but like a reporter on a story, a missionary on a mission, never mind that she could not name her cause. It seemed she was looking for something. She did not worry about the renewal of her teaching contract because its being terminated would finally give her a reason to pack up and flee. She was twenty-nine years old and unwilling to consider this place the backdrop for the rest of her life.

As an excuse for being a community, Pinetop had used mining and then timber industries. But that was over. Now those attendant structures hulked emptily on the hillsides as eyesores. Some nights they seemed to sneak closer, big boxes full of the void, square black windows and doors like holes punched in for a peek. The town had burned down twice in its one-hundred-year history, so there remained no interesting architecture, no quaint clapboard buildings or stately brick ones, nothing but the mountain of toxic mine tailings and the ravaged hillside where once there'd been a forest. A few towns away, the Apaches ran a gambling casino, and there was a large horse-racing trade in the vicinity, but neither of those lucrative businesses did much for Pinetop, although every Pinetop merchant sold T-shirts and postcards advertising both. Many of the locals seemed to think their town was about to be discovered by that most profitable of enterprises, tourism; little specialty shops popped up like flowers every spring -- espresso bar, chocolate shoppe, Christmas ornament boutique -- opening cheerfully with banners and bargains only to slowly wither over the summer and fall, the merchandise grown dusty, the clerk gloomy, the owner cynical, the crepe paper shabby and saggy, until the store-front stood desolate once more. Failure seemed its own thriving industry, like death.

On the highways leading in and out the national franchises lined up, jockeying for attention, pushed together like snap beads, the same eye-catching toy colors, red, yellow, blue, green. People in Pinetop considered it a coup when a fast-food chain selected their town for an outlet; they loved their Wendy's and their Jack in the Box and their Kentucky Fried. For the convenience of a drive-through window, they'd forsaken the downtown cafe, Dora's, in favor of McDonald's. Quaintness did not interest them. Charm was a little nothing you wore jingling on your wrist.

Plus, the wind blew. The mountains sat in such a way that a nearly constant wind howled through; pointed pine trees, those left standing, listed north-eastward as if yearning to give up and sail off, arrows into space. The gritty tailings, heaped in a barren yellow dune at the western end of town, flew overhead on particularly bad days, snicking against the window glass, thickening the air like flung salt, settling over the streets and yards and roofs. In the winter, it was snow that blanketed the ground, drifted against the east and north sides of houses, banked icy buttresses before windows and doors.

From the Windy City herself, Birdy should have been accustomed to the relentlessness. She'd hated the wind since she was a child, its cunning chill factor in the winter, its taunting tornadoes in the summer. But in Chicago you could huddle in doorways, escape into basements, dash between the high-rises, duck into steamy delis or crowded appliance shops. You could take solace in the fact that the wind swept away the litter and smog. The city fathers acknowledged its eminent domain; they heated the El stops and burrowed out parking lots underground; they called themselves Hog Butcher to the World, and girded their loins.

Here, people pretended the wind was not incessant. They walked out of their houses with tentative grips on their possessions, their hats and umbrellas and trash sacks. Their skirts flew up and their television antennas snapped, laundry defied the line. Both this year and last, everyone assured Birdy it was highly unusual, all this wind. They went around being astonished by it, exclaiming. She was suspicious of their wonder. She lived in a trailer, which rocked in the breeze like a bread box. Her neighbors owned aerodynamic A-frames, or peeling log cabins with portable carports lashed to them, or trailers such as her own, sitting atop concrete blocks and pink fiberglass bales, roofs dotted with old tires like sliced olives on saltines. It was not uncommon in Pinetop for houses to come rolling in on the highways -- and, conversely, for automobiles to rest in fields among the flowers and cattle. Everywhere you looked there were signs reminding you not to dump: DO NOT DUMP, as if you might be tempted, otherwise, to unload all of your garbage, right here, right now. Birdy's street, she learned after the first winter, was situated where the prostitutes used to live in tiny shacks called cribs. The remaining cribs looked like fancy, albeit dilapidated, doghouses, a whole vacant row of them, six places, each no larger than a mattress. This was the side of town where people owned roosters and motorcycles; in the mornings, they crowed and roared. Property was marked by the use of cyclone fencing or scrawny chicken wire, or, most mysterious of all, plastic gallon milk jugs filled with colored water, set wobbling on the ground in rows like giant jelly beans, grotesque Easter eggs the same faded pastel shades, pink, aqua, lilac, daffodil. What trespass were they capable of discouraging? The backside of Main Street, Birdy's neighborhood was so close to where Mt. Ballard and Mt. Ajax met that it did not see sunshine for the months of December and January. Farther, a kind of stream ran through, making things chillier.

It probably had a name, this shivering water, but Birdy did not know it.

The other side of town was the sunny side, and that's where the reputable people had always lived on a gently sloping, brightly lit hillside. Their streets bisected the incline like bleachers, on each row rested the square facades of two-story bungalows, barrackslike, militantly overlooking the spectacle of Main Street, and, behind it, Birdy's squalid turf. Only the upstanding could keep their balance over there; the rest slid, as in a landfill, toward the bottom. Pinetop High was located in the bleachers, a 1950s yellow-brick building designed like a prison or mental institution: massive, functional, impenetrable as well as inescapable.

But Birdy had moved here in a fit of defiant self-pity, whimsical exile, so her grim living arrangement suited her. Of course her side of town was where the hookers and the poor foreign miners had lived. Of course her pipes would freeze and burst; of course her gas bill would skyrocket -- her tin home leaked its heat like an old-fashioned pie cabinet. And in the humid late summer, the mosquitoes would descend along the riverbank to suck blood from whatever lived there.

"This town," Birdy would say to her friend, "it depresses me."

"Sadness," Jesús would agree, mildly, without emotion, the way their students said bummer. The symbol for grief, the shorthand recognition of others' pain.

Jesús had grown up in Pinetop. For a few weeks Birdy had thought he was named Zeus. "Hey" was just a way of calling him. Affably, since he was homegrown. "Hey, Zeus." That's how naive she was concerning her new state and its culture. The Spanish language still scared her; she was convinced people were discussing her as they chattered with each other in it, going fast just to thwart her. At a critical juncture, Jesús had fled Pinetop for Albuquerque, which passed as the area's big city. There, he developed sophistication and a sense of humor, became gay without suffering trauma, then returned, having maintained good relations with his former teachers, his parents, his old friends. Birdy thought Jesús was nothing short of remarkable; she wished her family and hometown liked her as much as his liked him. The only snag in his life was his need to speed off to Albuquerque every few weeks to spend a weekend. There, he picked up men, visited clubs, wore women's clothes, ate pills like candy. Then he was back, in his saggy innocuous pants and big sweatshirt, perfectly jolly. He never quit smiling; was that his secret? It cheered you up just to see his shining, apple-cheeked face. In Pinetop, he joined the fan clubs advertised on cable television and waited for UPS to bring him esoteric old movies that the local video store did not stock. He smoked clove cigarettes and listened to Barbra Streisand on obsolete vinyl albums. Birdy relished his friendship; in a larger town, it wouldn't have been possible. In a larger town, he would be a member of a group that excluded her, a group two notches hipper than she, but here, in little Pinetop, they became pals.

"A mom called me," Birdy told Jesús one day when they were alone in the teachers' lounge.

"Not a mom!"

"Mark Anthony's mom."

"That Mark Anthony," Jesús said. "What a babe."

Besides his famous name, Birdy hadn't particularly noticed the boy, who sat dutifully in her Social Problems and American Values section, a required senior class. The faculty called it Sock Probs and Am Vals, as if it concerned car engines, a course rotated among them; nobody enjoyed teaching it, too much reading was involved, and all of it dry, dry, dry. Birdy had caused a stir by introducing fiction texts to the curriculum, Invisible Man, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Scarlet Letter, those glum nobbles.

"What could she want?" Birdy fretted.

"You use the Lord's name in vain lately?"

"I think I might have said 'suck,' as in 'Your research essays suck.'" She hated conflict; she was prepared to confess to anything.

"You have a habit of blaspheming the American government."

"I know."

"You're in trouble, girl."

"A mom, a mom, a mom." Birdy laid her head on the lounge table.

"Don't you think Mark Anthony's a babe?" Jesús asked, laying his head down across from her so he could see her sideways. His eyebrows jumped, the way they did when Birdy seemed to be missing something obvious. He made a grin, which, up-ended, Birdy saw was a perfect rectangle, teeth like a package of peppermint Chiclets.

"I don't trust babes," Birdy told him.

"Interesting," he said.

Mrs. Pack, the school secretary, walked into the lounge then and regarded them suspiciously, as she always did, as if Jesús were still the student he'd once been -- impish jailbait -- and as if Birdy were the bad influence. They could not be up to anything good, with their faces on the tabletop. Other teachers called her by her first name, Edith, but Jesús and Birdy always said, "Good morning, Mrs. Pack" like brats.

This, Birdy decided, was the way she would stay young, by refusing to grow up.

Mrs. Pack told Birdy that her two o'clock appointment had just called to confirm.

"Wah!"

"Isadora Anthony" she added.

"Is she a good witch," Jesús asked, "or a bad one?"

Mrs. Pack pointedly did not answer, as if ignoring him might cure his irritating conduct. "I believe she said she was meeting with you, but our connection was bad. Is there weather?" All three of them looked toward the high windows, which revealed nothing certain.

"It's her phone," Birdy said. Yesterday there had been hissing on the line -- cheap receiver, thick walls, or the simple interference of the infernal wind -- then the woman had said, "Missus Stone?" in a long southern interrogative.

"Miz Stone," Birdy had answered, emphasizing it the way she hated her students to do, as if she were already an old maid.

Mrs. Anthony said, "Oh." More hissing. "Miz Stone? I was wondering if we could have a meeting? It's not about your class. It's another thing." She said "another" as if it were a girl's name, Anna Other. Birdy had agreed out of alarm, out of curiosity; now she invented a scenario in which Jesús and Mrs. Anthony's son Mark had become illicit lovers. Her heart thumped with the thrill of such a transgression -- and someone else's transgression, not hers. Then she formulated her own sober response...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date1998

- ISBN 10 0684839326

- ISBN 13 9780684839325

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Nobodys Girl

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0684839326

Nobodys Girl

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0684839326

Nobodys Girl

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0684839326

Nobodys Girl

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0684839326

Nobodys Girl

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0684839326

Nobodys Girl

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks156250

NOBODYS GIRL

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.95. Seller Inventory # Q-0684839326