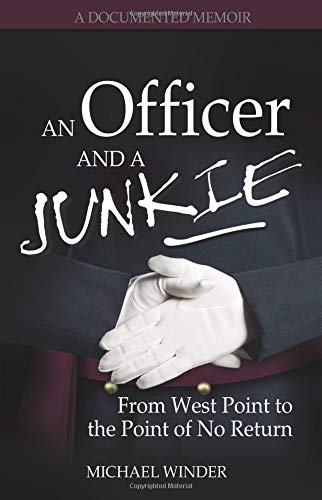

Items related to An Officer and a Junkie: From West Point to the Point...

Michael Winder longed to be a part of America's elite―to stand in The Long Gray Line as an officer in the United States Army. His quest for academic, athletic, and leadership excellence began as a cadet at the prestigious United States Military Academy at West Point. But before the end of his sophomore year, Winder buckled under pressure, and in search of an escape, he turned to alcohol and recreational drugs―eventually plummeting into debilitating and self-destructive abuse. Despite his inability to function without hourly doses of narcotics and alcohol chasers, Winder managed to graduate from West Point and earned a commission as an officer in the U.S. Army. An Officer and a Junkie is Winder's documented cautionary tale of his battle with substance abuse and dependency. With episodic, straightforward narrative, he pulls no punches in his confessions of what he did (and did not do) both inside and outside military walls, revealing his innermost delusions and most shameful acts. Once the years of self-neglect finally began taking their toll, the consequences were disastrous; Winder came to believe he was the reincarnation of Mexican impressionist painter Frida Kahlo and ultimately Jesus Christ.

When Winder finally does give up drugs and embraces sobriety, he receives what his doctors assure him is a lifelong sentence of antipsychotic and mood-stabilizing medication. But his fine intellect remains, as does his brutal honesty and his riveting and unforgettable account of his descent into madness.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Part One

Joiningthe Ranks

1996–1999

1

R-Day

July 1, 1996

This was probably a bad idea, I think.

We pass through Thayer Gate. Everything is gray. All around us are large, drab, gray buildings. Military police usher us through the gates. They wear camouflage uniforms, with black field boots, white gloves, and 9 millimeter (mm) pistols holstered at their sides. Their rigid movements, deadpan eyes, and sharp, well-articulated voices are far, far too real.

I'm in shock. What am I doing? I wonder. This is only the first of a thousand times today that I will ask myself this question.

It's Reception Day ('R-Day') at West Point. R-Day is a new cadet's first day of Beast Barracks, simply known as 'Beast,' the affectionate moniker given to the six weeks of Basic Field Training undertaken by new cadets. For most cadets, military training and education begins on R-Day, when they enlist in the military, complete in-processing, take the Oath of Enlistment, review medical records, and begin practicing drill and ceremony movements that include learning to stand at attention, marching, saluting, and turning.

I had visited the Academy twice before, for my physical exams. I saw spectacular scenic views, the school's well-known distinctive buildings, cadets in uniform, and beautiful statues and monuments dedicated to important historical figures and alumni such as Generals Dwight Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur, George Patton, and John Pershing.

On my previous visits I had not walked around the post or spoken with a single cadet about what the school was like, nor did I ever speak to any graduate. I had made a point of learning as little as possible, hoping that this might ease my trepidation and prevent me from changing my mind. I wanted to be a cadet, a part of the highly revered Long Gray Line, but I did not want to be dissuaded by the rigorous program. This was a challenge I deeply wanted to rise to, but I didn't have the confidence that I could to adhere to rigor and discipline, so I tried to avoid the knowledge of the specifics of training at all costs. Now everything looks so foreign to me. Everything looks so military. I think of Robert Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land. This is indeed a whole new world.

I am standing in the Holleder Center, on the floor of the Academy's basketball gymnasium, saying good-bye to my parents. I am determined to look calm, cool, and collected. I don't want to show how nervous I really am, especially in front of my dad―the six-foot-six, outspoken, tough-as-nails Jewish boy from the Bronx. My emotions are a weakness for me, an uncomfortable vulnerability.

'So, how are you feeling?' my father asks in his most relaxed voice.

'Good. You know. Fine.' I glance at my feet.

'Nervous?' he asks.

'No, not really. Maybe a little. But that's probably to be expected,' I say. Is my anxiety that obvious? I hope not.

'Of course it is.' He gestures vaguely to the hundreds of other new cadets saying good-bye to their families. 'Do you think any of these guys here aren't nervous about today? Of course they are! It's only natural. They're all going through the same thing. You're going to do fine.'

Looking around, I wonder how many, like me, are seriously questioning their choice. Did I make the right decision? What if it's too much for me? I don't want to fail. What am I getting myself into? The military? Me? Maybe I should just forget the whole thing? Is that possible? How would that look? My brain is working overtime.

'Michael, you're going to do just fine. We are both extremely proud of you and have tremendous confidence that you can do it,' my mother affirms.

'Thanks, Mom.'

'Michael, I just want to reiterate what your mother said,' my dad added. 'We are really proud of you. You showed great determination and perseverance to get here, and it says a lot.'

About a year ago, I had received a rejection letter from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Around my family I had been nonchalant about attending. Secretly, though, I yearned for the opportunity to do something that would set me apart from others, make me 'special.' I felt proud just telling people that I'd applied. I couldn't imagine how it would feel to say I was accepted, or better yet, that I had graduated.

My maternal grandfather, who lived in Germany, first made me realize the prestige of the Academy. Even though he lived in a small farm town on the other side of the world, he simply couldn't stop raving about West Point.

When I got my rejection letter, the verdict was in. I was average. Indeed, my parents were quite pleased at the notion of my attending the Academy, but it was I who secretly dreamed of being a member of this prestigious club. I was crushed. I walked into my room, lay down on my bed, and cried.

A few days later my father asked me if I'd given any thought to reapplying the following year.

'No. Absolutely not,' I said. 'I didn't really want to go anyway. I'm actually pretty happy about going to UConn.'

Another few days went by, and my father asked me again.

'No. It's really not for me. Anyhow, there's no way Congressman [Christopher] Shays would give me a second nomination. And even if he did, there's no way they'd accept me. They made their decision.'

Another few days went by, and my dad asked me again. I told him, 'Well, my physical [examination] score was pretty low, so maybe if I improved it enough I'd have a shot.'

The following day I announced, 'I've got an intense workout plan set up. I'm going to start interval training, to get my speed up for the shuttle run, and strength training, so that this time I can do more than just two pull-ups.' My father smiled.

I spent the summer training every day, confident that I could do much better. Shortly after starting classes at the University of Connecticut, I took West Point's physical entrance exam once again, this time scoring above average in all categories. My fine physical score, combined with two dean's list semesters at UConn and the fact that I had not been dissuaded by rejection, was enough to land me a congressional nomination for the second year in a row and, ultimately, admittance to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

My grandfather couldn't have been prouder.

Now, standing in the Holleder Center, I am aware that my dad is still talking and I haven't been listening. 'You're going to do great. Just take it one day at a time. All right?'

'Yeah, thanks.' The booming voice of the officer with the megaphone is suddenly instructing us to say our good-byes.

'I think they're calling your number,' my father says.

'Yeah, I gotta go.'

'How about a hug?' my mother asks. I dislike public shows of affection; however, it is impossible to say no to her. My mother, a very petite, reserved, kind, and soft-spoken woman from a small German farm town who moved to America in her early thirties, is the exact opposite of my father.

'I love you. You're going to do just fine,' my mom whispers in my ear.

'Thanks.'

'All right, Mike. This is all you,' my dad says. 'Take care. And give us a call as soon as you get a chance.'

'Yes, please do give us a call,' my mother chimes in.

'Will do. Bye.'

With a halfhearted smile I grab my duffel bag and turn around, joining the countless other new cadets exiting the back of the building.

Passing through the doors, I cross into a new reality. I am no longer a civilian, I am a new cadet. Upper-class cadets, dressed in pristine white uniforms, usher us onto buses. There is not a hint of a smile or amusement on any of their faces. The upperclassmen look deadly serious as they shout orders at us.

For those relatively unacquainted with the military, as you might imagine, forceful corrections are a necessary part of our military's training process. Simply put: one must learn how to take orders before they can give them. The gravity of this training cannot be overstated, as it will almost inevitably play a role in one's combat decisions, thereby affecting the life and death of his or her troops.

'There will be no talking.'

'Head and eyes forward.'

'Form a single-file line and move with a purpose onto the bus.'

Amid the flurry of directions, I scramble into line. As I find my seat on the bus, a cadet gives us the drill.

'New cadets, listen up. When I am talking, you will not be talking. When I am not talking, you will not be talking. You will not speak unless spoken to. If you have a question, you will raise your hand. You have four and only four responses that you may use when an upper-class cadet speaks to you: 'Yes, sir,' 'No, sir,' 'No excuse, sir,' and 'Sir, I do not understand.' Do you all understand?'

'Yes, sir.'

'I said, do you all understand?'

'Yes, sir!'

'Good. When an upper-class cadet speaks to you, you will pop off [reply with a loud, firm voice]. Understood?'

'Yes, sir!'

'You will address all male upper-class cadets as sir and all female upper-class cadets as ma'am. Understood?'

'Yes, sir!'

'When this bus stops, you will all grab your gear and quickly exit in a single-file line, forming four equal ranks [rows] in front of the bus. Understood?'

'Yes, sir!'

'You will keep your head and eyes forward, you will not speak to your buddy, and you will move with a purpose. Is that understood?'

'Yes, sir!'

'Good. Today is going to be a long day, so remember to drink a lot of water and stay hydrated. Understood?'

'Yes, sir!'

Looking around, I notice that the smiles on the faces of my peers have rapidly faded. At least I'm not alone in my apprehension.

I'm from Westport, Connecticut―a small, affluent, predominantly white town, about forty-five minutes north of New York City. I grew up hating conformity, authority, discipline, stress, and physical fitness; the latter was especially grueling in light of my twisted spine―a thirty-one degree scoliotic curve. I came to West Point for the challenge; it was time to step out of my comfort zone and time to move to the top of the pack. I want to be a part of something exceptional. West Point cadets are the elite, our nation's finest―the best of the best.

When the bus stops, we quickly exit and form four ranks outside, as instructed. An upperclassman, a blurry white cyborg, indiscernible from the rest, steps in front of us and begins bellowing orders.

'All right, listen up, new cadets. From now on, when you are not in a fall-out area [a place that plebes can be 'at ease'], which includes the academic buildings, the gymnasium behind you, and your rooms, you will move with a purpose. Your hands will be clenched and arms locked out straight, swinging at your sides like so. You will keep your head and eyes forward and you will move out. When you pass the upperclassmen you will greet them with our regimental motto for Beast: To the Limit. And when you are in formation, you will stand at the position of attention, unless instructed otherwise. Is that understood?'

'Yes, sir!'

'All right, now I want all of you to drop the bags you are carrying right where you are. You are leaving them here.' He pauses while we comply.

'Good. And you're probably going to hear this about a thousand times today, but remember; it's going to be a long day, so drink plenty of water and stay hydrated. Now, starting with the rear rank, I want you all to move in a single-file line into the gymnasium behind you to begin your in-processing.'

The process of stripping away our civilian identities begins. I shed my battered jeans and Pink Floyd T-shirt and don black army shorts and a white crewneck T-shirt. Soon after, I put on my army-issued dog tags for the first time. It feels good. I am going to be a soldier―an officer.

I spend the next few hours getting shots, reviewing medical records, and filling out paperwork. After that, I wait in countless lines, steadily filling up the large bag they have given me with numerous articles of army-issued clothing and accessories.

After this phase of in-processing is complete, our groups are attached to specific cadre (the upper-class cadets in charge of us), and I am taken to the cadet barbershop.

As soon as the clippers hit my head and the hair starts falling to the floor, it dawns on me that this is for real. This isn't a one-day affair. This is for keeps. The barbers don't care about preferences; there are more than a thousand new cadets whose hair must be cut today. It is fast and furious. There is an insane amount of hair on the floor. One second I am sitting down, and the next second the barber is pulling off my apron and ushering me out of the chair.

Regardless of the hairstyles we all have coming in, no male cadet leaves the barbershop chair without a 'high and tight,' and no female cadet leaves with hair touching her shoulders.

After the haircut, my group's cadre marches us back to the barracks. We enter Central Area, a large blacktop space in the heart of West Point, enclosed by extremely large (and extremely gray) buildings on all four sides and thus invisible from the outside. Visitors are not permitted in 'the Area.'

New cadets are frantically scuttling about while a torrent of voices reverberates throughout the vast courtyard. Upper-class cadets are shouting orders to their squad members. I see new cadets practicing marching, making facing movements (right-face, left-face, about-face) in place, and having their salutes adjusted. Others are 'locked up' by upperclassmen, receiving forceful corrections at the position of attention. Still others are standing at parade rest, reading their Knowledge Book.

Parade rest is a variation of a standard position assumed by a soldier in which the feet are placed twelve inches apart, the hands are clasped behind the back, and the head is held motionless and facing forward. When we are at parade rest, we are often instructed to read the Knowledge Book, which is more than a hundred pages of West Point facts, mission statements, and excerpts from famous speeches. New cadets must memorize this book and recite it to their squad leaders during Beast. This position consists of a minor variation on the standard stance: one hand holds the book out in front while the other maintains its normal position on the small of the back.

Things are starting to get hazy. I dread our next task: reporting to the Cadet in the Red Sash. He is dressed in the same perfectly white uniform as the others, except that he also has a dark red sash tied around his waist. He looks ominous. We are given very specific instructions on exactly how we are to report to him. It is not terribly hard, but we are all a bundle of nerves, and this is our first time being put on the spot individually. If a new cadet makes a mistake, the Cadet in the Red Sash stops him or her, makes the necessary corrections, and sends the new cadet back to do it again. The new cadets who return look decidedly frazzled. Miraculously, I report to him properly on the first go-around. This is a pleasant and unexpected surprise. Maybe I'm going to be good at this!

The Cadet in the Red Sash tells me that I am in Charlie Company and to go rep...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHci

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 075730639X

- ISBN 13 9780757306396

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages371

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

An Officer and a Junkie: From West Point to the Point of No Return

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_075730639X

AN OFFICER AND A JUNKIE: FROM WE

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.87. Seller Inventory # Q-075730639X