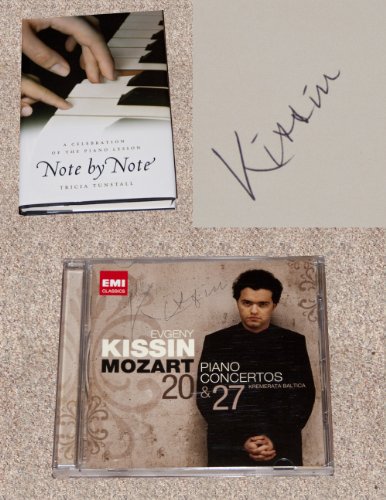

Items related to Note by Note: A Celebration of the Piano Lesson

Note by Note is in part a memoir in which Tunstall recalls her own childhood piano teachers and their influence. As she observes, the piano lesson is unlike the experience of being coached on an athletic team or taught in a classroom, in that it is a one-on-one, personal communication. Physically proximate, mutually concentrating on the transfer of a skill that is often arduous, complicated and frustrating, teacher and student occasionally experience breakthroughs-moments of joy when the student has learned something, mastered a musical passage or expressed a feeling through music. The relationship is not only one-way: teaching the piano is a lifelong endeavor of particular intensity and power.

Anyone who has ever studied the piano-or wanted to-will cherish this gem of a book.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Beginnings

Jenny sits on my piano bench. Her feet swing freely; they will not reach the floor, not to mention the pedals, for another year or two. She stares at a note on the page of music in her open lesson book, her eyes wide, her tongue caught between her lips. "A," she whispers to herself. The seconds file slowly by, and then at last the third finger of her left hand presses a key. A furtive glance at me; was it right? I nod. She nearly smiles, and then her eyes return to the page. More seconds, loud with silence. "G," she murmurs.

For a six-year-old a piano lesson can be an act of courage. Every note is an occasion for worry, a tiny drama involving risk and consequence. Fingers perch awkwardly on the keys, so likely to be the wrong keys, or the wrong fingers. The black circles of the notes caught in the implacable grid of lines on the page are so easily mistaken for other notes tangled between other lines. There are numbers that mean fingers and there are numbers that mean beats; it is hard to know which is which. Sometimes I have to remind Jenny to breathe.

Do you remember your piano lessons? Most people do. There tends to be a visceral immediacy to these memories, a sensory sting. "Caramels," says my friend Eileen, "my teacher ate caramels while I played. She weighed three hundred pounds. I never got to eat a caramel." My sister-in-law Suzanne remembers the bumpy brick floor of the sitting room where she waited for her lesson, and the way the stained-glass windows in the piano studio cast a tawny light on her music. My teenage son Evan has a vivid image of the Ssips juice boxes at the house of his piano teacher (who was, needless to say, not me); as a six-year-old, he was deeply impressed both by the wondrous spelling of the word on the boxes and by the fact that he was not offered one. Long after one has forgotten how to play the Minuet in G, the memory remains of the piano teacher's perfume or garlic breath, the tassels on her lampshade, the sharp bark of her dog.

The piano teacher... or the flute teacher, or the violin teacher. In the course of a modern American childhood, there are very few occasions when a child spends an extended period alone with an unrelated adult. Classroom learning, athletic coaching, Sunday school -- all these forms of instruction are group activities. But the music lesson is one on one. It requires a weekly session alone together, physically proximate, concentrating on the transfer of a skill that is complicated and difficult, often frustrating and frequently tedious, but that every now and then opens suddenly and without warning into joy.

In recent years there have been attempts, of course, to replace this arcane ritual with truly modern forms of instruction. There are instructional videos, printed manuals, on-line courses, all purporting to teach one to play the piano in twelve short months or ten easy steps. Ask any piano teacher: we are not worried. Our phones ring regularly with potential new students. We know that, mostly, people do not want "interactive programming" or "user-friendly software." People want piano lessons.

Even now, in a time when very little current popular music involves an actual person playing an actual piano -- even now, parents want their children to have piano lessons. Adults wish their parents had given them piano lessons. Perhaps most surprising, children want piano lessons. There lingers in the culture a sense, however unexamined or anachronistic, that a truly complete education must include lessons in playing a musical instrument -- the violin or flute or trumpet, sometimes, but most frequently, because it is the most accessible, the piano.

What is the enduring appeal of the piano lesson as a basic ritual of American childhood? I have spent a great deal of my life as a piano student, pianist or piano teacher, and I can only begin to guess at the reasons. What I can say -- what I do know -- is that piano lessons are not only about music but also about trust and confidence, chaos and order, spontaneity and discipline and patience, sometimes even about love... and once again, and always, about music: its beauty, its power, its capacity to convey profound emotions beyond the reach of words.

This is true from the beginning, the very earliest lessons. Jenny on my piano bench is not only learning where G is, she is learning to take risks. She is learning to trust me and, eventually, herself. And she is experiencing beauty, because when G follows A just exactly as it should, in the context of an emerging melody -- well, it may not be profound, but it can be beautiful.

My first piano teacher was Dorothea Ortmann, daughter of the director of the Peabody Conservatory. When I was six she was terribly old, maybe even fifty. Her row house on Saint Paul Street in downtown Baltimore had three stories, and I sometimes thought I could hear pianos being played on all three floors simultaneously. I did not know who else was playing, but I decided that she had six grand pianos, two on each floor. Six would not have been too many for Miss Ortmann, whose life was clearly dedicated to the art of pianism in the grand European tradition. I would not have been surprised to learn that when her students had gone and she was left in dark brocaded solitude, she drifted up and down the stairs playing all the pianos, all night long.

Miss Ortmann had a dimly lit sitting room where on a side table sat a number of those once-popular miniature toy animals constructed of tiny segments of hollow wood through which a kind of rubber band was threaded; the animal stood upright until you pressed a circular disc beneath its base, when it would collapse. If you pressed the base gently and just on one side, you could make the animal bend its front or back legs, or even nod its head. I took these toys as evidence that the firm and methodical Miss Ortmann had a fun-loving side. Now, it occurs to me that she was encouraging finger dexterity in her waiting students.

I never did see her fun-loving side. She was gracious, she was cheerful, but she was very strict; I was transfixed and intimidated. Now, as I sit next to Jenny watching her spindly fingers, her fragile profile, it occurs to me that I was as acutely exposed to Miss Ortmann as Jenny is to me, and that her strict demeanor may have been her way of distancing herself from my vulnerability.

While in Jenny's eyes I am certainly very old, I am not Miss Ortmann, not as serious and formal. For one thing, I am chattier. In every first lesson, for example, I ask my new student what music he or she listens to. I don't believe it would have occurred to Miss Ortmann to ask such a question, although I would have loved to tell her about my little record player decorated with nursery rhyme characters. It played only forty-fives, and if there was dust on the needle -- there was usually dust on the needle -- the music would sound like something coming over a transistor radio at sea. My parents had given me a thick red leather volume of bound record sleeves filled with recordings of great classics, with the odd and wonderful result that to this day, Little Miss Muffet reminds me of Rachmaninoff's Second Piano Concerto, Red Riding Hood of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony. As for the recording quality, the first time I heard a symphony played live in a concert hall, I think I vaguely missed the static.

Had she asked, I would gladly have shared all of this with Miss Ortmann. My beginners, however, tend to have trouble with the question. "What music do you listen to?" I say, after they have been introduced to middle C and counted all the Cs on my piano. Usually, the answer is a blank stare. They don't know what music they listen to; they don't know that they listen to music.

And maybe they don't listen, but they do hear music. They hear it all the time. They hear it with every television commercial, every video game, every movie, every trip to the supermarket or the mall. They are literally bombarded with musical stimulation -- but usually as accompaniment to a visual image or as part of a sell or, very often, both. Listening to music, as an activity sufficient unto itself, is something very few children have experienced in our visually overstimulated culture. So my first job is to rescue music from its ubiquity -- to pull it from the background to the forefront, free it from its uses. "What's your favorite movie, Jenny?" I ask when she assures me she never listens to music. "Harry Potter," she says instantly. I play her the first phrase of "Hedwig's Theme," a tune from the soundtrack. She is startled. Shaken loose from larger-than-life cinematic imagery and played on the austere geography of the black and white keys, the melody emerges as something simply to listen to. "Play it again," she says. I play it again. No flying brooms, no charismatic wizards, nothing at all to look at. Jenny sits, listening.

"What's your parents' favorite song?" can work too, for younger children especially. Maggie, for example, a round-faced eight-year-old, can recite all the lyrics of "Here Comes the Sun," including the exact number of repetitions of "Sun, sun, sun, here it comes." And Jenny knows every word of Abba's "Dancing Queen." They live with music; they've just never been conscious of hearing it.

Some beginners come with more awareness. "I listen to my brother's heavy metal," they tell me, or "I listen to The Phantom of the Opera" (as if it were a genre all its own, which perhaps it is). "I listen to jazz," says the son of a professional trombonist. He sighs. "All the time."

A lucky few come singing. Rebecca, for example, nine years old and Broadway-smitten, insists on ending lessons by reversing seats with me and singing "Where Is Love?" or "Castle on a Cloud" to my accompaniment. She tends to sing, in fact, all the way through her lessons; when she plays a melody without singing it, she says, "I can't hear it." This orientation may become problematic when she gets around to playing a Bach invention. For now, it is a distinct advantage: it helps her understand pitch direction...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 1416540504

- ISBN 13 9781416540502

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages224

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Note by Note: A Celebration of the Piano Lesson

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition 0.7. Seller Inventory # bk1416540504xvz189zvxnew

Note by Note: A Celebration of the Piano Lesson

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.7. Seller Inventory # 353-1416540504-new

Note by Note: A Celebration of the Piano Lesson

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks446675

Note by Note: A Celebration of the Piano Lesson Tunstall, Tricia

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.7. Seller Inventory # Q-1416540504