Items related to I Am Because You Are: How the Spirit of Ubuntu Inspired...

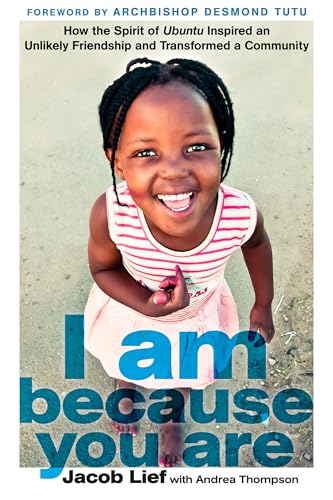

I Am Because You Are: How the Spirit of Ubuntu Inspired an Unlikely Friendship and Transformed a Community - Hardcover

Their vision? To provide vulnerable children in the townships with what every child deserves-everything.

Today, their organization, Ubuntu Education Fund, is upending conventional wisdom about how to break the cycle of poverty. Shunning traditional development models, Ubuntu has redefined the concept of scale, focusing on how deeply it can impact each child's life rather than how many it can reach. Ubuntu provides everything a child needs and deserves, from prenatal care for pregnant mothers to support through university-essentially, from cradle to career. Their child-centered approach reminds us that one's birthplace should not determine one's future.

I Am Because You Are sets forth an unflinching portrayal of the unique rewards and challenges of the nonprofit world while offering a bold vision for a new model of development.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Andrea Thompson is an editor and author whose writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The San Francisco Chronicle.

The Meaning of a Dress

In many ways, Zethu Ngceza was like any other kid in the townships of Port Elizabeth. Her family struggled to make ends meet--her father was a municipal worker, and her mother was unemployed. They lived together in what was once a men's hostel for migrant workers, sharing the small space with other families. Still, they were a happy family, and laughter filled their home. Then, in 2004, her father died three months after coming down with an HIV-related illness. The following year, her mother fell sick, also with an HIV-related illness, and died after only two months. Zethu's life turned upside-down.

At fourteen, Zethu became the head of her household, taking care of her younger brother, Star, and sister, Lungi. "I started asking myself some questions," she later recalled. "Questions like 'What am I supposed to do? Should I just go? Should I just run away? I've got dreams. How can I face this thing?' But I told myself, 'These are my siblings. This is my brother, this is my sister. They deserve the best.'"

For a few years, Zethu had been participating in programs that Ubuntu Education Fund ran in her school. She'd grown to trust Zuki, one of the health educators who worked there, and so she confided to her that she and her siblings had been orphaned. Zuki quickly acted. Fezeka, an Ubuntu household stability counselor, visited Zethu's home and figured out what the three children needed immediately. Of most concern was the safety of their home. Burglar bars on the windows, a better door, and a sturdy lock went on the checklist. She brought them a food parcel, with fresh vegetables and pantry staples. They needed better light so they could study, and new uniforms. She assured Zethu that her school fees would be paid.

Zethu wrestled with feelings of anger and guilt, along with her grief. Why was she left alone to take care of her siblings? How could she be a mother to them when she was their sister? Small and slight, she hardly seemed strong enough to carry the responsibility.

Yet, she did. And when she felt overwhelmed or anxious or afraid, she called Fezeka. If they'd run out of cooking oil, or her sister's skirt was too small, or her brother had begun acting out in school, she'd come to Ubuntu for help. And, sometimes, she'd come to Ubuntu to forget all her responsibilities for an hour or two and just be a kid.

I first went to South Africa when I was in high school, and I fell in love with the country as soon as I walked off the plane. It was 1994, in the midst of the turbulent transition from apartheid to democracy. The energy, the pride, and the promise of the New South Africa inspired me. When I returned as a student at the University of Pennsylvania, I met Banks Gwaxula, a schoolteacher with an ebullient personality who offered me a place to stay and helped me find work in the townships. He changed my life. I lived with him for three transformative months, and by the end, I knew what I wanted to do: be a part of the New South Africa. The banter on the street, the smells of red earth and burning coal, the energy of the people, the overpowering congestion inside the urban townships, and the enormous space outside of them--it's intoxicating and invigorating. There's a lawlessness that can be terrifying, and of course has had negative consequences, but also imparts a sense of freedom. The country and the continent have something that goes deep inside, that's inescapable. No matter how far you travel, as they say, the dust of Africa stays on the soles of your feet.

With their extreme poverty and organized chaos, the townships, it seems, shouldn't function. But they do. I was drawn to the people's absolute determination to make good on all of the promises of the anti-apartheid movement. Banks and I decided--with the best intentions but remarkable naivete--that we wanted to help children achieve their dreams. We didn't know the rules of development; we didn't care about the external measures of success. And we didn't see ourselves as saving anyone. We simply wanted to help create a level playing field for the children we knew in the townships, and we believed that if we could do that, there was nothing they couldn't achieve.

As our organization grew, we realized that what so many of these children really needed was a parent. Whether their own parents were gone or unable to take care of them--because of poverty, HIV, or mental illness--having someone to provide the basics of life was the missing piece. They needed someone to give them anything and everything they needed, like any parents would if they could. After all, hours of tutoring or a health education class meant little when rain leaked through the roof and there was nothing to eat for dinner. For me, Zethu embodied this truth. When I first met her, I couldn't believe how much this tiny girl had to bear each day. Even with Ubuntu's help, life wasn't easy--she had to find time to study, to clean her own and her siblings' clothes, to cook, to help them with their problems. Zethu faced each day as a feat of endurance. And it was immediately apparent just how vulnerable she and her siblings were: They had nothing to fall back on, no safe harbor if something went wrong.

I grew to realize over the years that Zethu and her siblings, in many ways, embodied the struggles all of Ubuntu's clients faced, and their outcomes showed both the triumphs and the challenges that go into trying to intervene in a meaningful way. Not every child will go on to university or a career; sometimes the forces of mental illness or peer pressure or the growing pains of being an adolescent throw up roadblocks. Sometimes they are insurmountable. But in Zethu, Lungi, and Star, I see every child that Ubuntu works with and for--every one who has achieved more than she ever thought possible, and every one that fell along the way.

In 2006, the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) asked to meet some of our children who had been orphaned and left to take care of siblings. We arranged an afternoon for forty of these clients to sit in our courtyard with representatives from CGI and tell them about their lives. Zethu sat among the group. The representatives were taken with her vibrant smile and calm confidence, as well as her dedication to her siblings. After a visit to her home, they invited her to speak at their midyear meeting in New York. She delivered a captivating speech to a roomful of influential thinkers, nonprofit leaders, and philanthropists, and charmed former President Bill Clinton with her precocious poise. It was a heady experience. When she came home, it was difficult to return to life as usual: school, caring for Star and Lungi, studying at night. She began to skip classes, run around with boys--act, for once, like a sixteen-year-old.

Those of us at Ubuntu felt the same way any parent dealing with any teenager would feel: exasperated and exhausted. There's a limit to what you can do to curb self-destructive behavior, and to a certain extent, being present and loving is the best you can do. Everyone at Ubuntu cared deeply for this family, and Fezeka wasn't the only one who reached out. Eventually, Zethu realized that she needed to put herself back on track. She rededicated herself to school, came back to Ubuntu for extra help in the afternoons, and started to think about university.

We all celebrated with Zethu when she started her studies in managed accounting at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. And as she approached her final exams, we held our breath: She was so close to a diploma, one tangible marker of success.

Finally, the moment arrived. Zethu checked her scores with a knot in her stomach. One after another, she read the results: Passed. The relief swept over her. She was going to graduate.

In the back of her mind, underneath the relief and excitement, there was a small kernel of sadness. With graduation came the graduation ceremony. To participate, you had to buy a gown, and most students' parents treated it like a special occasion, with a new dress, a trip to the hair salon, nice shoes. But Zethu didn't have a mother or father to take her shopping, and she knew she didn't have the money. She resigned herself to reality: She would be content with knowing all she had achieved, and leave the celebratory trappings to others.

Her first call was to Fezeka. "I've passed!" Zethu told her. "I'm going to graduate, can you believe it?" Over the years, Fezeka had watched Zethu struggle, fail, pick herself back up, and go back to work. Over all these years, Zethu never acted entitled or grasping; she accepted help with grace, but she often held back from asking for more. Fezeka knew what went into graduation: the hair, the nails, the clothes. But she also knew that Zethu was conscious of all the ways in which she was more fortunate than others and tried not to ask for anything that wasn't vital.

Fezeka asked, "Zethu, don't you need new clothes?"

"Oh, I don't have money," Zethu answered.

"Did you ever have money before?" asked Fezeka.

"No."

"So when you need something, what do you usually do?"

Zethu laughed a little and said, "I ask you. But this isn't a priority. When you don't have money, you don't do these things."

"No, ma'am," responded Fezeka. "That's nonsense. You only graduate once, and you have to look like a graduate--any parent is going to make sure their child looks right."

Early one afternoon, I was in my office in the Ubuntu Centre, where I was entertaining a donor. He'd come down to visit--basically, to kick the tires of our operation and see where his money was going. Lots of donors have this impulse: They want to feel and see and hear what exactly their thousands of dollars have built. On this visit, I'd shown him around our multimillion-dollar, award-winning new home, which provided much-needed space for our after-school programs, tutoring, clinic, and pharmacy. We'd thrown a braai--a South African barbecue--in his honor, where he'd been able to meet many of our staff and students. Over a plate of roasted pig, he had heard about university plans, summer internships, and new jobs.

The donor's generosity didn't blind him to weaknesses in any organization, and he asked lots of probing, perceptive questions, gauging the return on his investment. Were we cost-effective? What impact did one of his dollars actually have? How were we reducing unnecessary costs? We'd been reviewing the details of Ubuntu's financial health for nearly an hour when a conversation outside my open door caught our attention.

"Zethu is graduating in a few days, and we want to buy her a new dress along with the graduation gown, and to take her to get her hair done," Fezeka was saying. "This is a big milestone. I think we should make her feel special."

"I don't know," we heard Jana, our program director, reply. "I'd love to do it for her, but does it make sense to spend the money there?"

"It's such a huge day for her, we have to celebrate," Fezeka responded. "You're right, of course," Jana said. "Let's look into it."

As they walked away, the donor looked at me with his eyebrows raised. "You can't possibly be considering buying one child new clothes for graduation, can you?" he said. "With all the strains on your budget, how could you possibly justify something so frivolous for a single girl?"

It was a fair question. What Ubuntu does--intensive, cradle-to-career services--costs a lot. In Zethu's case, her decade in our programs cost close to $65,000. In the world of development funding, where today's buzzwords are "scale," "sustainability," and "cost-effectiveness," this is a shocking number. Adding to that number by buying a special dress for a single occasion? Unthinkable.

But clearly Ubuntu doesn't follow the well-trod path. Later that afternoon, I talked to Fezeka, Jana, and other team members about giving Zethu a new dress. The unconditional feeling was "Of course we should do it! This is exactly what we do."

I thought again about Ubuntu's mission. It's more than metrics of cost and benefit, of return on investment--that's only one part of it. What we do, pure and simple, is help raise children. And part of raising children involves fielding those unexpected requests for things that may not be necessary, but make a child feel special.*

So, yeah, let's get Zethu that new dress. Let's make her feel amazing on this incredible day when she will become the first person, not only in her family but also on her entire street, to graduate from university. Let's celebrate this accomplishment with her. Let's feel proud, like any parent would feel proud, and let's help her feel proud, too.

On graduation day, Fezeka went to pick up Zethu for the ceremony. She hadn't been able to go dress shopping with Zethu; Zethu had teased, "Good! You'd make me buy an old-lady dress." When Fezeka arrived, Zethu was putting on her final touches. After a few minutes, she emerged with a radiant smile, wearing a gray-and-navy dress that fell to just above her knees.

For a moment, Fezeka was silent. Then she said, "Wow--is that you? How come you are wearing this short dress?" She laughed, delighted at Zethu's transformation.

Zethu laughed, too, and said, "Ah, that is why I didn't want you to go shopping with me! This is what is being worn, and it's going to be under the gown anyway."

As she crossed the stage to collect her diploma a few hours later, Zethu paused to look out at the audience. Her sister, Lungi, was there, and her neighbors in the township, who had done all they could to watch out for her over the years. Fezeka was there, with tears in her eyes, and so was one of her teachers from high school, who had always treated her like a daughter.

After all that she'd been through, all the days of being overwhelmed and angry and sad, Zethu thought, this moment felt like the start of a new life. A pretty dress didn't make her a success, but it reminded her she'd become one.

* To be clear, Ubuntu also provides a high return on investment: Every dollar that Ubuntu Education Fund invests in a child results in real lifetime earnings of $8.70 and a $2.20 net gain to society.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRodale Books

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 1623364493

- ISBN 13 9781623364496

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages224

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

I Am Because You Are: How the Spirit of Ubuntu Inspired an Unlikely Friendship and Transformed a Community

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition 1.1. Seller Inventory # bk1623364493xvz189zvxnew

I Am Because You Are: How the Spirit of Ubuntu Inspired an Unlikely Friendship and Transformed a Community

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.1. Seller Inventory # 353-1623364493-new

I Am Because You Are: How the Spirit of Ubuntu Inspired an Unlikely Friendship and Transformed a Community

Book Description Condition: new. Illustrated. Book is in NEW condition. Satisfaction Guaranteed! Fast Customer Service!!. Seller Inventory # PSN1623364493